“I once won the Super Bowl,” he remarked. “I had the time of my life on that field.”

Kyle Harden was a lanky, fresh-faced, scabby-kneed, 8-year-old kid in his first season of peewee football, and he was on top of the world.

“Lame or not, to this day I still count that as my best game,” Harden said.

The memories Harden has of making that one “glorious tackle,” celebrating with teammates as the clock winded down, and hoisting that brand new, gold-painted trophy above his head, almost never were.

“My parents didn’t want me to play football,” he confessed. “They said it was too dangerous.”

It is often said that injuries are just a part of the game, but how do parents weigh the risks and benefits of the contact sport?

For the parents of  the now 19-year-old, collegiate football player, it was not the fear of a broken arm or a mild concussion but rather the Type 1 diabetes that plagued their son’s body.

the now 19-year-old, collegiate football player, it was not the fear of a broken arm or a mild concussion but rather the Type 1 diabetes that plagued their son’s body.

“I was really sick,” Harden said. “I lost around 20 pounds, was thirsty all the time and had to urinate frequently. These were all signs of it.”

The telling signs were not hard to miss, especially for his mother, Maggie Harden, who is also a Type 1 diabetic.

However, even with an obvious family history of Type 1 and worsening symptoms, no hospital was giving Harden a diagnosis.

“My mom couldn’t bear to see me like that so she did something risky that could’ve sent her to jail,” Harden remarked. “She gave me insulin that wasn’t prescribed to me. … It helped.”

That risky move all paid off. Her son was officially diagnosed as a Type 1 diabetic.

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disorder, in which the body’s immune system attacks cells in the pancreas which make insulin, a hormone that controls a person’s blood sugar; it enables people to get energy from food. There’s nothing a person willfully does that triggers it.

According to the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) of the 26 million Americans with diabetes, an estimated 3 million have Type 1. This kind of news is life-changing for most.

Since he was young, pricking fingers and shots of insulin have always been a part of Harden’s home-life; since he was 8, it has been a part of his daily routine.

“It’s been a blessing to have been around my mom and brother,” Harden said. “I’ve never been alone with dealing with it.”

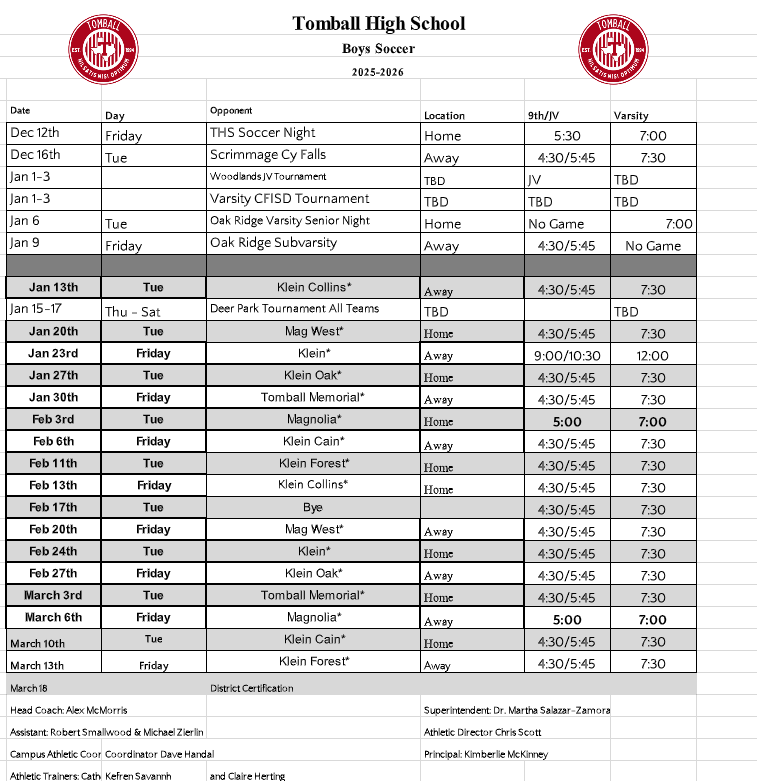

That is until he headed to Lake Charles, La., and traded in his red and white Tomball High School football jersey for a new color scheme, the blue and gold of McNeese State.

The two-time 2nd team All-District, 1st team Academics and recipient of his high school’s 2011 football season MVP and Heart Award never used his disease as an excuse.

“If I mess up in a play it’s because I did something stupid, but that’s just typical me, not because I feel sick,” Harden joked.

Though he seems to have it all under control, the inside linebacker knows he’s not invincible. Harden acknowledges that no matter how well his blood sugar is maintained, at the end of it all, he is at the disease’s whim.

“Sometimes I can feel it coming on during practice,” Harden said. “No one really wants to stop after every play to check their blood sugar.”

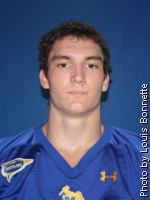

At 6-foot-3 and 225 pounds, Harden doesn’t look like his body is in a constant battle with itself; in fact, he looks stronger and healthier than the average male. It comes as a bit of a shocker when his teammates first see him coyly pull out a syringe in the middle of the locker room and inject himself. Many are left in disbelief. Many have never seen a fellow athlete have to do anything of the sort.

“Once my team mates know some of them can’t believe I still play football,” he said.

“I tell my coaches but most of them forget, and that’s fine, because I try to not bring it up. I’m here for football.”

Football plays just as big of a role in the life of the pre-med, inside linebacker as Type 1 diabetes does.

“[Football] is more than just a game. It’s a big part of my life. It’s taught me to how interact with people, about leadership, to be passionate, and everything else that has made me successful so far,” Harden explained. “I got a full ride here [at McNeese State University] because of it. I don’t know what I would do without it.”

Going from grade school ball to the collegiate level does not come without great difficulty. Ask any athlete: What is one of the main differences between high and college sports? Speed. Harden learned that in the first few minutes of practice.

“The speed is unbelievable. Everyone is the best from where they come from, just like you,” Harden said. “It’s a humbling experience.”

McNeese State finished the season 7-4, capped by a big 35-0 win in the season finale against Lamar. His jersey will be put away for another off-season. But those dreams of holding a trophy above his head remain.