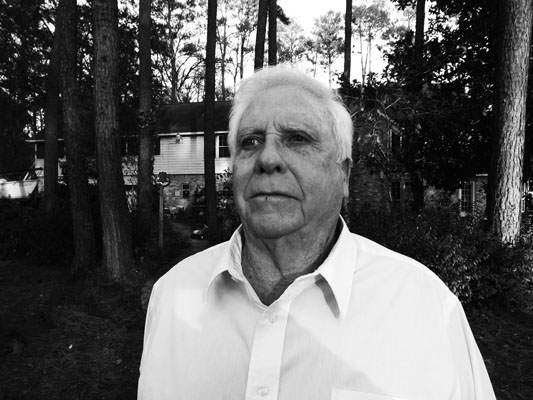

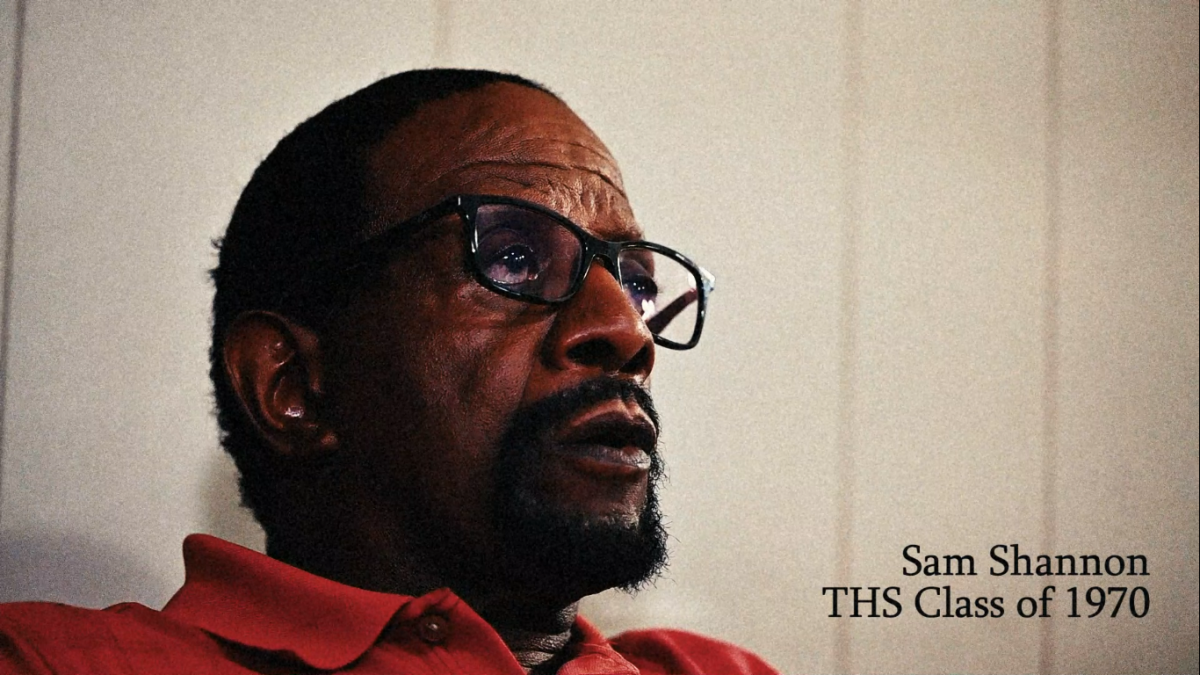

He sat in his usual spot – a red and blue plaid rocking chair placed in the corner of the room, next to the kitchen in the home that he built himself. The television is muted; he is watching the news, his usual station. Occasionally, he leans in and cups his hand around his left ear.

“I’m sorry, say that again?” he says every-now-and-then. “I’m about to get a hearing aid.” When asked his age, he sits up proudly in his chair, “I’m 77 years old!” his voice rumbles.

Wood paneling and floral wallpaper embellish the walls of his house. Toys and playthings left out by grandchildren are sprawled about in the main living area. Knick knacks and porcelain dolls cover shelves throughout the house, including Mrs. Francis’ glass case, one she proudly keeps.

Sometimes, she decorates the inside with small, dazzling white lights. They hold her favorite items which are exchanged frequently to a new theme every-so-often. During bright days, sunlight shines into large windows surrounding the stone fireplace on the slanted ceiling. On some summer days, the light is so bright that it becomes easy to forget the use of light bulbs.

Despite all this, most gatherings are contained in the kitchen, the heart of the household, as well as John’s favorite plaid chair which resides next to the dinner table and across from the TV.

Light also shines brightly in this sectioned room which leads into the cooking area of the kitchen. The windows reside in the eating area at the head of the dinner table. The plaid chair rests its being against the wall, right next to these windows.

If one were able to judge a person’s life by a single look into a window, this window would surely be a candidate. If one could not determine that in the Francis house resides a long-time married couple by front yard appearances, they would certainly know it once shown the back.

The first to be noticed are old cars; the kind that are seen on TV shows and perhaps internet auctions, the only difference being that most of them would need to be restored to qualify for such things. A 1935 green Chevrolet cross standard with black fenders, a 1941 gray Chevrolet, a metallic green 1941 Cadillac convertible, a 1946 maroon Chrysler Highlander (which happens to be his favorite as it is “well built”). These cars, among others, are some of the oldest. The list goes on.

There has to be at least 10 automobiles at first glance, old and new, and if one were to ask John himself, he would have to take a moment to count in his head, then give up and go outside to his garage and count each car, then the ones in plain sight, then the ones in the driveway and then to his second garage.

Mixed in along with old cars, rust, all sorts of tools and random appliances are his wife’s items. An odd and beautiful backyard, a first-time visitor might describe it as a unique experience. There are many pots placed in seemingly random areas; some empty, some the carrier of a variety of plant life.

There is a brick patio which can be seen from the kitchen window which gives the viewer a pleasant sight: an outdoor glass table with many assorted knick knacks and plants placed atop it, including a metal bottle tree, its stems bearing thick blue, green and clear bottles collected throughout the months in which Mrs. Francis had a phase, in which its beauty and culture would not let her rest until she had had her fill of it.

And, of course, her patio would not be complete without a shelf. Small and wooden, it holds painted clay figures and knick knacks not dissimilar to the many more in her house. Beyond the patio leads a small stone trail to the rest of the backyard and pool area, seemingly mysterious and shaded by commonplace pine trees, but somehow an open area. Deer are common creatures to be seen roaming.

In his backyard, John works on his cars. It’s a hobby of his, as it has always been – not that he has particularly been fixing things his whole life, but he sure does know how a machine works. He is reminded of his time as a rocket engineer in his earlier days, as this year NASA has begun to bring back old F1 engines from storage for testing, learning from past designs in hopes of reconstructing a modern engine.

When asked about his childhood interest in mechanics, his white, straggly eyebrows push together as he says in his most honest voice: “I’ve always had an interest in mechanical objects.”

His thirst for knowledge was evident in his young years. He couldn’t count how many times he dismantled his father’s car engine, his young eyes taken aback by the complex structure of the motor. He can recall, however, being 14 years old and infatuated with his father’s brand new 1949 Ford and its shiny midnight blue exterior. He just had to prop open the hood of that car.

“I didn’t really know what I was doing at the time” he admitted with a chuckle, as he recalled, “turning gears out of line.” His father wasn’t too happy when he found a mechanic’s fee of $10 on the monthly credit card bill.

“It doesn’t sound like a lot, but that’s what, a hundred dollars now-a-days?” he said. His eyebrows raised and pushed together as he racked his brain for old memories beginning to resurface from decades of storage.

And as it turns out, Mr. John Francis didn’t just rip his father’s car engine apart. Heck, he tried taking apart a train when he was 12 years old. A small section, that is, but a train nonetheless.

It happened to be a certain antique steam engine on display in Silverton, Colorado that caught his attention. He was staying at a lodge with his family when he became obsessively curious about the inner workings of the brilliant machine. And from his own father’s toolbox, he tinkered away at the steam engine’s valves with the “borrowed” wrenches and screwdrivers, desperate to figure out where and how the steam was escaping.

Oh, sure, he angered a few people in this devious act. But like an angel, he courteously put each part back together and in its proper place as the fuming adults gathering around him began to smile.

The seven-year-old John Francis was just as mischievous. He had just received a brand new Western Flyer bike for his seventh birthday. It was a beautiful shade of red, painted with white stripes; but what really fascinated him was the machinery itself.

He reminisced over his fond memories with a sparkle in his eye as he described the marvelous chain and how it kept the wheels turning, but not the pedals, and how the brake system, with its cleverly designed rear sprocket, allowed him to come to a peaceful stop just by slightly pedaling backwards.

He had to dismantle the whole thing, find out how it worked – how could he resist? Every piece was unraveled, and it became a puzzle for him to figure out how to rebuild his bike. It took him weeks.

And some feat it was for him, as he proudly recalled this as being the first time he really understood how a machine worked. By the time he had finished putting his bike back together, he knew all of its ins-and-outs.

Turn the clock further back. Whatever demon possessed him to take apart his parents’ brand new alarm clock, he’ll never know. He couldn’t have been more than five or six years old. Its shiny exterior excited him; the enticing ticking of the minute hand perhaps ignited some sort of brilliant flame in his mind.

But even after many decades, he can still recall the most exciting feeling; perhaps his first mechanical discovery being a spring in the back of a clock placed atop his parent’s table, as he examined the fine engineered specimen with all of its intricate gears turning so delicately.

He had taken and stretched out one of its springs so far that “It wrapped around the whole room!” he exclaimed, the young-at-heart man’s lively hands reenacting the scene from his mind, his pointer finger whirling around in the air wildly.

But as his parents walked into the room to find their brand new clock being picked apart, his six-year-old hands managed to painstakingly ravel the spring back tightly into its original shape, or as close as he could get it, while his parents stood by. But it was too late; he was already hooked on mechanics. He swears that the clock, however, never worked quite right after that.

John graduated from college when he was 27. Shortly after college, with his degree in mechanical engineering and BS in mathematics in hand, he was hired to work for Rocketdyne, a rocket engineering company. (the F1 engine in the Saturn V he designed with his team that blasted Neil Armstrong into space can be seen on Google images at the front of the building).

John was 27 when he first heard of the news that the US was to enter the race to the moon. He didn’t believe it would happen. It was after a day at work that he came home to watch the president on national TV give a speech about the impossible.

A hot day in Houston in 1962 on the campus of Rice University had the audience standing on the bleachers of a football stadium behind the president’s podium waving their hands over their faces, their eyes squinting into the sun, wiping their sweat with handkerchiefs.

John Kennedy leans in to the microphone, “President Pitzer, Mr. Vice President, Governor…” he begins, his voice sturdy and strong, though squinting into the sun with the rest of the audience.

He gives a brief history of humanity. He emphasizes the importance of technological advancement. Surely he is to announce something big.

Jokes are made about the scalding heat, jokes are made about sports. But then there is a change in atmosphere. Kennedy raises his voice, “We choose to go to the moon” he says. Nobody laughs. Though this statement may have been used in jokes countless times before, the goal of going to the moon suddenly became a real and serious topic.

Perhaps Kennedy had a glimpse of the future that day as he stood in the sun in a dark blue suit and looked onward. “It will be done in this decade” he says. The audience cheers, their eyes filled with excitement, one can only imagine what went through their minds.

“Many years ago” he waves his open palm across the air, “the great British explorer George Mallory, who was to die on Mount Everest, was asked why he wanted to climb it. He said, ‘Because it is there.’” he clenches his fist in the air firmly. “Well, space is there, and we’re going to climb it, and the moon and the planets are there, and new hopes for knowledge and peace are there.”

The suited president was serious. The idea of reaching the moon was no longer a joke, but a goal set by the president of the United States himself that was predestined to be reached. And it did happen before the decade ended.

John Francis became part of this great plan unknowingly, at first. As he was part of the team designing an F1 engine as part of a five-engine rocket (thought to be a missile at the time), he assumed that it would be used for military purposes – perhaps, in the case of war. Though with rumors of how the moon landing would be carried out around town and especially in the office, he had no idea what exactly this engine would be used for until later in the planning.

“Sixty-six thirty-three Canoga Park, California” John recited, more than once. His memory was sharp; he had a mind for numbers and detail. This is the address of Rocketdyne. “You can see that place on Google earth!” he would say, leaning in from out of his chair, his eyes wide, as if a picture had appeared in his mind in that moment.

John loved his job. He swears that every morning, he would wake up excited for another day at work, and while driving his car there, he would ask himself: “Well, what do I need to learn today?” He felt like he was on the “most exciting adventure in the world”.

John had left Rocketdyne and moved onto another rocket company, Lockheed, when the moon landing occurred. “I didn’t really think we could do it” he said with his eyebrows raised. There were so many things that could have gone wrong that he feared the worst; he thought the rocket would crash on impact.

There was only one word to describe John’s reaction to the landing as he watched the TV for hours to see the whole broadcast: Surprise. The next day at work, there were what rocket engineers called “splashdown parties”, as the F1 engines were released before hitting the atmosphere to “splash down” into the ocean.

The engineers celebrated hard work, they celebrated possibly the greatest success of the century, they celebrated because they knew they were part of the great American system. They symbolized American ingenuity. That day was forty-three years ago. John still believes that the moon landing “changed the country”.

John Francis worked a total of 11 years in the field of rocket engineering before moving onto another career in home development. If someone were to ask him why he moved on from his former career, he would say “I already learned everything I needed to know about rockets”.

That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.